Some of my recent posts have mentioned my excursion into sewing clothing from the 1830s. Most recently, in September, I posted about making a corded petticoat to help support a fashionable 1830s silhouette. I also shared a reminder about the fabric I’ve had in mind for an 1830s dress since I bought it seven years ago. It’s finally time to share the finished ensemble created with that fabric!

Today’s post is going to focus on the construction of this dress, but, never fear, upcoming posts will share more finished garment photos as well as construction details about the bonnet.

There is a lot of information about this dress to share and many photos of the process, so I hope you’re ready for a lengthy post!

Inspiration

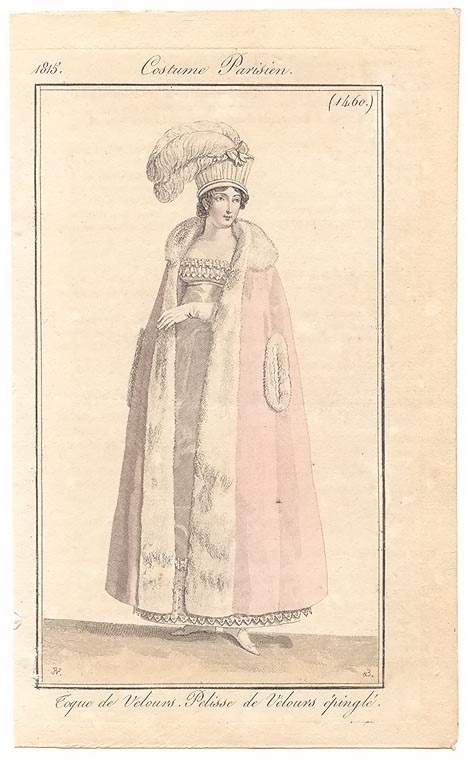

As you probably guessed from the title of this post, this dress is from the year 1834. The trimming details and shape are directly inspired by the dress pictured below, which is in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The V & A Dress is dated to 1830-1834. From a style perspective, this makes sense as these are the years from this decade with the largest sleeves, but it is also around this point in the decade that sleeve fullness starts to slide down the arm. This look that is just beginning to show in the V & A dress, which achieves the falling look with the addition of the mancherons at the top. The mancherons both practically and visually push the fullness of the sleeve off the shoulder.

What is a mancheron? The Oxford English Dictionary has the following entry):

mancheron, n.

1. French Heraldry. A sleeve used as a charge. Obsolete.

2. A piece of trimming on the upper part of a sleeve on a woman’s dress. Now historical.

Patterning

The pattern for this bodice is based on patterns contained in Janet Arnold’s Patterns of Fashion 1 and Norah Waugh’s The Cut of Women’s Clothes. I was able to start with my basic darted 1860s bodice and adapt it for the 1830s using information about grain line, dart placement, etc. from the books. This worked well because I know the basic darted bodice fits in areas that can be fussy to fit such as neckline, armhole, etc. and those things (in the 1860s) are still very similar to the shapes from the 1830s.

The sleeve pattern is from Plate 12 (page 84) in The Workwoman’s Guide (published in 1838), which can be viewed on Google Books here. I used the big circle sleeve (Figure 8–shown made up in Figure 7) and varied the top shape so that it forms a downward V shape to allow for my mancherons, which are patterned based on the V & A inspiration dress.

The ladies at American Duchess created a very helpful video discussing sleeve shapes from the 1830s, including showing mockups of a few different sleeve patterns from The Workwoman’s Guide. It is wonderful for seeing how the flat patterns turn into 3D shapes, which I found to be very helpful as I dithered about sleeve patterns.. You can view the video here. Lauren also has a blog post talking about 1830s sleeves, which shows the pattern I chose to use in various stages of its construction, from being flat to being made-up.

The skirt is based on information from the same books as the bodice pattern. It is made of 3 panels of my 45″ wide cotton fabric.

Construction Method Disclaimer

I chose to construct this dress in the mid-19th century way of separate bodice and skirt. This is odd for the 1830s (in fact, I can’t think of any examples that are done this way) as they are usually sewn together to make a one piece dress. However, as I was pondering sleeve options and considering my yardage I was faced with an exciting prospect.

There are so many sleeve variations in the 1830s–super poof, takes-a-while-to-get-used-to-looking-at elbow poof, meticulous pleated details as the poofs are reduced and contained… I wanted to make more than one! Also, I had 10 yards of my beautiful reproduction cotton and I expected my 1834 dress to only use about 7. What would I do with the last 3 yards? That’s not enough to make another dress. But… it is enough to make another bodice, even with giant 1830s sleeves that use a full yard for each arm!

I decided to make one skirt with two bodices, so in addition to this 1834 dress I also have an 1838 bodice halfway completed. It is a variation on a theme, using mostly the same bodice pieces, but with a different front style and different sleeves. More on that in the future, but for the purposes of this post it is an explanation for the fact that the skirt of my 1830s dress hooks to the bodice in a way that is common in the mid-19th century, as you can see below. (The loops on the skirt waistband blend really well with the pattern on the fabric, but you can see them if you look really carefully.)

Skirt Construction

As I mentioned earlier, my skirt is made up of 3 panels of my 45″ wide cotton. They are carefully pattern matched to keep the scrolling consistent across the panels and to help hide the seam lines. They’re not perfect, but they are pretty darn close.

Two seams are on each side of center front and one is at center back. The two front seams have french seamed pockets set into them below the cartridge pleats. This is wonderfully helpful while wearing the dress! I made sure to make the pockets big enough to hold a phone, keys, etc.

The fullness of the skirt is cartridge pleated to the waistband. I find that this quantity of cotton is weeny looking when cartridge pleated to a waistband without a little help to create loft, so I sandwiched a single layer of cotton flannel into the pleats to help them have a little bit of puff. I just used scrap flannel from my stash for this–the fun dot print pictured below. This is the top of my skirt pressed and ready for pleating!

Here is the skirt in the process of being pleated. The top edge is left raw and folded over the flannel before I ran two rows of parallel stitches to form the pleats.

I absolutely eyeball my cartridge pleats! My stitches are vaguely even but I really don’t worry too much about that. I mark the quarter points of the skirt and waistband and then adjust the pleats to fit. No math for this process!

The waistband has a single layer of canvas inside (a scrap from a decorating project) to help stiffen it and provide stability for the cartridge pleats and closures. This is machine stitched to the cotton where it will not show.

The cotton is then wrapped around the canvas and whip stitched in place. I finished the waistband entirely before whip stitching the cartridge pleats in place.

Bodice Construction

The construction of this bodice is pretty straightforward as 19th century bodices go, though I spent a bit of time searching out photos of extant dress interiors from this decade so I could see how they were finished (or left with unfinished edges!). I found these dresses featured on All The Pretty Dresses very helpful, especially as they have interior views: late 1830s green/blue/red cotton print dress and early 1830s brown dress.

There are other inspirational dresses on my Pinterest board for this project, as well. Many of them are held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Those are excellent because you can really zoom in on the photos to look at details, but unfortunately they don’t often show interior views of the dresses.

The hardest part about this bodice was the pattern matching! It was mind boggling to keep the flowers growing upwards, match the wave, keep the dark pink flowers at corresponding places, and keep some parts on the bias and some on the straight.

For example, here is my first attempt at the front bodice, which is cut on the bias. It’s not awful… but it’s just not quite right, and that bothers my eyes.

I very carefully tried again…

And was able to get this, which I was much happier with!

And I was able to use the reject front piece to cut out a pocket piece (and later a bit of bias as well)… no waste here!

Here is the front piece after flatlining (the fronts, side backs, and backs of the bodice are all flat lined with muslin), stitching the darts, and putting cording down the center front seam.

Ah yes, the cording! There is 1/16″ cotton cording in most of the bodice seams (front, side back, shoulders, armholes, neckline, and to finish the cuffs). This detail is taken directly from extant 1830s dresses.

My cording is made up of bias scraps, some as small as about 4″ long, that are pieced together. The cording is machine stitched. I made it with even seam allowances for most of the seams, but thought ahead and offset the seam allowance for the neckline cording, to make it easier to turn it under and whip stitch later. The photo below shows the neckline cording (on the top) and regular seam cording (on the bottom).

Here are the side back pieces with the cording attached, before being sewn to the back pieces. As you can see, I carefully matched my pattern across these two pieces as well.

And here is one side back sewn to its corresponding back, with the cording in the seam. Even across these pieces my pattern matching is pretty good, especially at the bottom!

And the back! It also makes me very happy, but was a super mind boggle to figure out! I have a flap that overlaps past center back, covering a pleat on the other side that will anchor my loops. I found this detail on a number of 1830s dresses, including this 1835-1836 dress at The Met and this c. 1837 dress at The Met.

It doesn’t look like much until it’s lined up to be closed… and then it’s perfect!

The final step was to finish the bottom. I wanted to have a self fabric waistband on this bodice, as with the bodice at the V & A, so that I would have the option of wearing my dress with or without a belt, while still having the visual change of pattern in the fabric.

The outer waistband and inner muslin facing encase the bottom seam allowance of the bodice. They are machine stitched at the top, have graded seam allowances, and then the muslin is whip stitched along the bottom.

Sleeve Construction

With the bodice mostly assembled, I moved on to the sleeves. These are not flat lined.

The sleeve is given shape by the use of sleeve puffs. I made my sleeve puffs in 2018 and posted a tutorial about how to make them.

I upgraded my sleeve puffs for this ensemble by giving them ties to attach to the armsceye of the dress so I can control the height that they sit at. This is essential for getting the right shape poof with this sleeve style. Looking into a sleeve, here is one sleeve puff tied in place.

I edged my decorative mancheron and cuff zig zag with narrow lace before attaching them to my sleeve. The cuff zig zags are sewn on by hand, while the full tops of the sleeves are gathered and machine sewn to the mancherons (you can see a the seam allowance from this seam in the photo above).

After the trim was added to the cuffs, I sewed cording to the bottom edge and then a muslin facing to finish everything off. This allows me to have nicely finished edges for the sleeve openings, which extend up about 8″ and allow for the tight fit of the forearms.

Here’s what that looks like flipped up and ready to be slip stitched along the top edge. You can see my hand sewing from attaching the cuff zig zag.

So… I got this far and realized that my sleeve was too narrow (even though I’d had no trouble in my mockup!) and my hand wouldn’t fit through the opening! Even if I made the opening higher, the sleeve edges wouldn’t butt, but would have a gap!

It’s good to have extra fabric… Having extra allowed me to make the decision to cut off the old forearm pieces and piece on new ones (with careful pattern matching, of course!). This meant redoing the cuff trim and finishing, but I couldn’t find a better solution. The seam hides under the crazy big sleeves, so it’s really not noticeable at all (even if I hadn’t pattern matched the seam!).

Finishing

Finally, after these various successes and challenges… the dress was done! Here are some more photos of it in its finished state.

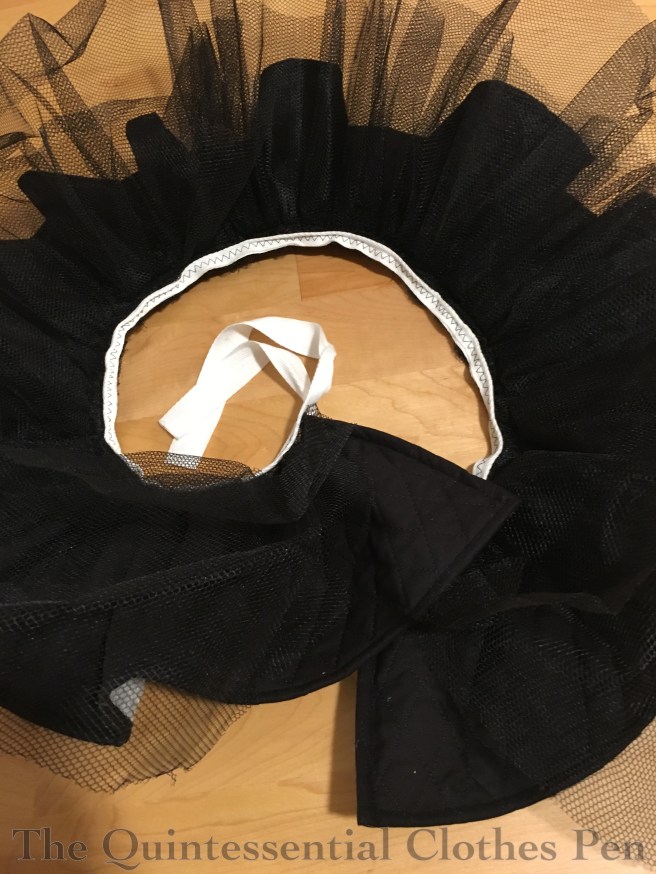

This is the inside of the bodice with the skirt attached. You can see machine stitching, seam allowances mostly left unfinished (they really don’t fray at all), neck binding, closures, etc.

This closeup shows a shoulder seam, as well as the neckline and armhole finishing. The bias on the neck is turned under and whip stitched. The lace is sewn on top of that. The armhole seam allowances were trimmed and then roughly whip stitched to hold the layers together. You can also see a little square of the twill tape tie for the sleeve puff (it is sewn to the armsceye seam allowance below the shoulder seam).

Here is the finished cuff opening. Hidden under the zig zag are the hooks that correspond to the loops on the muslin facing.

This is the center back opening with all of the closures in place. Those hooks really do camouflage well on the brown scroll, don’t they? Doing the closures this way leaves lots of seam allowance at center back for me to make alterations in the future if I need to.

This photo shows the inside of the skirt and bodice. Specifically, you can see the raw edge of the top edge skirt seam allowance folded to the inside (the skirt is intentionally shorter in the front than in the back, which you can see in the varied top edge seam allowanced length), the french seam of the pocket, and the skirt opening, which is simply an opening in the back seam (no placket on this skirt, the fullness of the cartridge pleats easily hides the opening).

One last photo! This is the cartridge pleats and bodice waistband from the exterior. Cartridge pleats are always visually intriguing to me and I also love how the waistband of the bodice is perfectly cut to show off the scroll and flower pattern.

After so many construction photos, here is a reminder of what the completed dress looks like from the exterior. I’m looking forward to sharing more photos in future posts!

Thanks for sticking with me through this very long post!