I made another pair of stays!

This pair is a reaction to many of the things that went wrong or that I didn’t like about The Stays of Fail (which I’ve posted a whole series about: the background, construction, and patterning, though the lessons learned post is still forthcoming) as well as a chance to try out ideas from Patterns of Fashion 5 and all of the information I’ve learned about stay-making over the last 10 years or so.

The Background Story

I made a pair of stays about 10 years ago, so I figured I had some experience… Such hubris! We can always learn more things.

The old pair is well documented in old blog posts, but I would like to point out that since I made those stays I’ve learned so much–about what fabrics to use, what the construction process should be, etc. I’ve also changed size in the last 10 years, so my old stays (which always had a gap, intentionally), now hardly reach around my sides. It’s no longer a gap, it’s a chasm!

I don’t wear 18th century clothing that often, so making these work has been fine… The last time I wore them was to Versailles in 2016. They’re still pretty comfortable, they just need a very long lace to bridge the chasm!

However, in the last few years I’ve developed grand plans to make 1780s and 1790s clothing and I wanted a better fitting support structure to go underneath. I thought I’d use the knowledge I’ve gained, along with the invaluable information in Patterns of Fashion 5 (only published recently in 2019), to make a new pair of stays. (If you want to know more about the book, I rave about its amazingness in more detail in this blog post.)

Contemplating My First Pair Of Stays

With the knowledge I’ve gained over the last 10 years, I suppose I would call the old stays ‘smooth covered’ stays that are fully boned with cane. I wanted to machine sew the channels but picked a lovely patterned silk for the exterior that I didn’t want machine channels on top of, so that’s where the smooth covered idea came from.

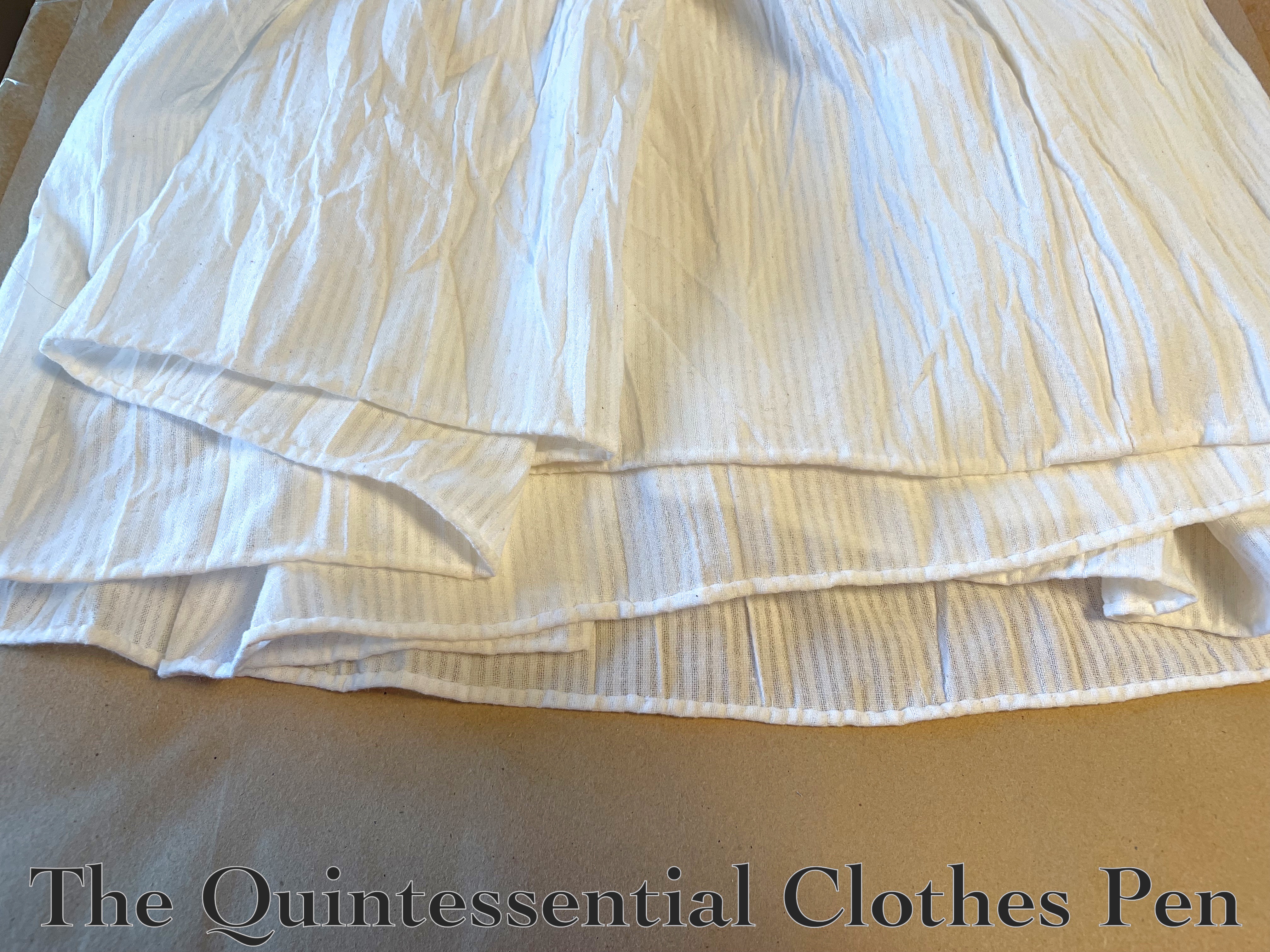

At the time I made the stays, I didn’t know what the purpose of the narrow tapes covering the seams was (now I know: it’s to cover what shows of the whip stitches used to attach the pieces together when the stays are hand sewn, as they would have been), so I inserted piping to approximate the look. It’s definitely not historical, but my best guess at the time. And, some of my piping isn’t long enough to extend into the binding… Below, a view of this old pair of stays (more photos in this past blog post).

Speaking of which, the binding is bias twill, which isn’t terrible, but is much more of a 19th century practice than an 18th century one (18th century stays seem to be most often bound in tapes or leather).

The one thing I did do well was create hand sewn eyelets for lacing, though they are set up for x lacing as opposed to spiral lacing (the latter being more common in the 18th century for the functional closure of stays).

Patterning The New Green Stays

For the new stays, I wanted to try the drafting method detailed in Patterns of Fashion 5 on page 155 as opposed to sizing up a gridded pattern and adjusting it to fit. The instructions are easy to follow, although determining exactly what height the measurements should be taken at takes practice, previous knowledge, and/or trial and error.

My measurements are: bust 40, waist 33. When I used those measurements, the pieces were a little large, so I adapted the pattern to use these measurements: bust 36, waist 30.

The other measurements I used to create the pattern were:

width of CB to armhole: 6″

width of CF to armhole: 9″ (maybe this was too big)

underarm to waist: 6″

CF top to waist: 6.5″

CF waist to bottom of peak: 5″

CB top to waist: 9.5″

CB waist to bottom of peak: 4″

CB top to top of side hip: 15.5″

I felt the patterning was quite successful! I was able to use my measurements and easily adapt the pattern to fit my back in a way that did not cause discomfort (as was the problem with the Stays of Fail early on in the process).

Constructing The New Green Stays

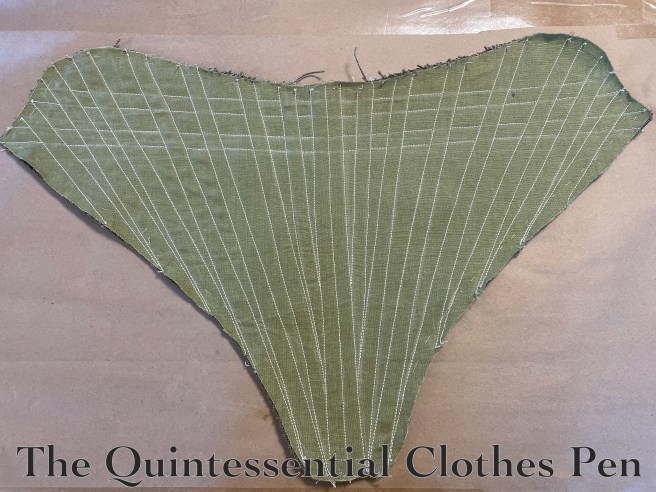

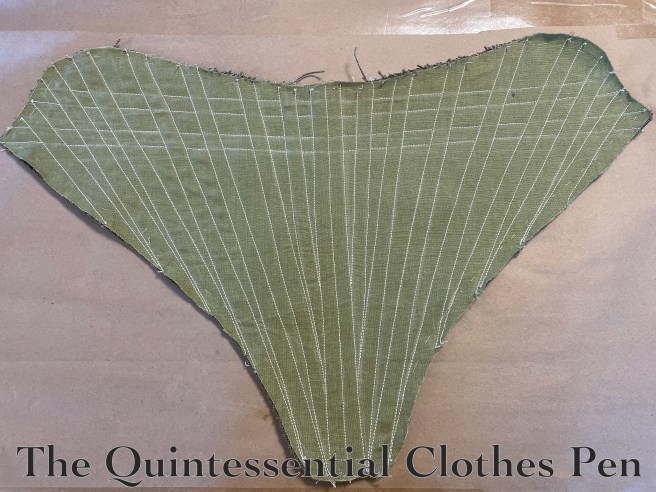

These stays have an exterior made from leftover avocado green linen from the stash. Additionally, there are two layers of heavyweight, coarse army green linen that make up the structure of the stays. This is also from the stash–it was gifted to me and is too heavy for most garments I make. The weight is great for supporting stays, though!

Here are my inner lining pieces set up on my limited green linen scrap.

Constructing The New Green Stays

The new stays are half boned. I chose to machine sew the channels with buttonhole weight thread (I wasn’t about to spend a million hours hand sewing channels again after just doing that for The Stays of Fail).

I like the look of the heavier thread, as opposed to regular weight sewing thread. The channels are boned with full width zip ties (none of that cutting them in half nonsense like I did for The Stays of Fail, either).

As an experiment, I chose a boning pattern with both vertical/diagonal bones as well as bones that run horizontally across the chest. That means that my boning channels crossed.

I carefully started and stopped my stitches to line up at the corners of the crossing channels and left my tails loose, to be pulled to the inside and knotted by hand later in the process. I did the same with my thread ends at the raw edges, so that my channels would be beautifully even with no backstitching (it helps with the illusion that the channels are hand stitched and not machine sewn).

In places where the boning channels crossed, I added an additional piece of coarse linen on the inside of the stays. This allowed me to have separate boning channels for the different directions, which was helpful in keeping the crossing points from becoming too bulky.

After the boning channels were in, I put in the bones that would no longer be accessible after the seams were sewn. Then, I machine sewed my pieces together. (This project was about making successfully patterned stays more-so than completely hand stitched ones!)

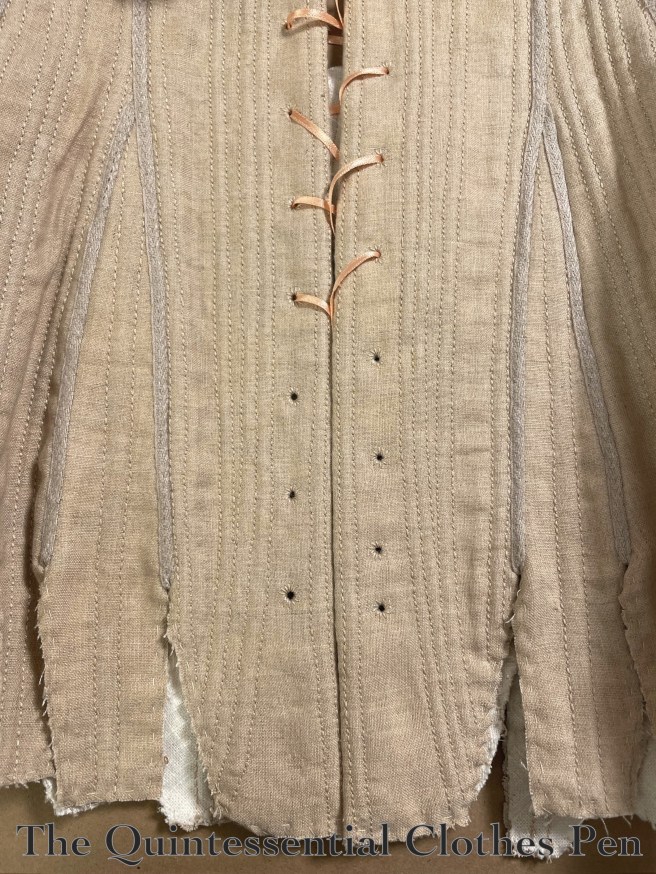

Following that step, the remaining bones were pushed into the channels. I also hand stitched the eyelets around this time (I made them pretty big for ease of lacing–the ones I’d made on The Stays of Fail are pretty tiny!). Below, my eyelets are marked and my edges are tidied.

Next, I basted around the edges of the stays to keep the bones in place, covered my exterior seams with woven linen tape, trimmed my edges, whip stitched my edges, and bound the edges of the stays in ¾” linen tape.

The stays looked like this on the inside at this point.

And like this on the outside.

I also added extra laters of reinforcement over the belly, as seen in extant stays. These are graduated in size and made of the same coarse linen.

Some stays also have wooden busks to further stiffen the center front. Given that these already have modern methods, I chose to use an extra heavy, ½” wide steel bone for my busk. It is inserted under the extra layers of linen and stitched in place, as you can see below.

The final step was to line the stays. I used a natural colored cotton/linen blend from my stash. The tabs are each lined with a small bit of fabric (you can see that in the above photo). Then fabric was laid out on the inside of the main body of the stays, traced, and cut for both sides. The lining pieces are all whip stitched in place.

Here is a closeup of the back edge and tabs, with eyelets, binding, and full lining.

Below, a closeup of the top edge of the stays as I pinned the lining in preparation for trimming it to the correct size.

The seams on the inside do not correspond to the exterior seams.

Finished Stays

These new stays fit pretty well and are generally comfortable.

The front width wound up being a bit wide for me across the top, but otherwise they are good.

Final Thoughts

I like the horizontal boning across the front. The only downside to that is that the stays don’t fold in half for storage!

I had such a fun time deciding what pattern-making decisions to make. (What grainline to use on each piece? What boning pattern to use? Straps or no straps?) I couldn’t include all of the ideas in a single pair of stays, and so I have plans to make another pair, in a dark yellow from my stash. The someday-yellow pair will allow me to tweak the fit of the front as well as play with alternate patterning ideas. The pattern and materials are still out… it’s just a matter of finding the time and inspiration!

P.S. Stay-making Resources

This is not comprehensive, by any standards, but I thought it might be helpful to collect some links that I’ve found useful for anyone who wants to know more or see other people’s stays. (These blog posts were especially useful for seeing the process when I didn’t have PoF5 on my cutting table! That gives you a sense of the fact that this blog post started at least 3 years ago!)

Blogs showing the creation of similar stays:

- The Sewing Goatherd: 1780s Stays Using Scroop’s Augusta Pattern (and stiffening her own innards, too!)

- Rococo Atelier: 18th century speedy stay making tutorial using a sewing machine, this is part 1, this is part 2, this is part 3 (great photos and tips, this pair of stays also uses the PoF5 drafting method and machine sewing)

- The Fashionable Past: 1780s Stays Tutorial (not quite the same shape as my stays, but the process is basically the same and this has lots of great photos of each step)

- Rockin’ The Rococo: 18th century stays (the shape is earlier than mine, but the process is basically the same and this has lots of great photos of each step)

- The Mantua Maker At Midnight: Making Stays 1730-1780s (this is earlier than mine, but the process is basically the same and this has lots of great photos of each step)

- Atelier Nostalgia: Late 18th Century Stays (these are more similar to my Stays of Fail in some details–the tape straps and center front opening, for example–, but the general construction information is applicable to lots of stay projects)

Videos about stays:

Blogs with information about stays:

Pattern suggestions: