One of the five pieces of my Vernet Project was creating the silly up-turned-toe elf shoes in the fashion plate. Clearly, these are not shoes that could be purchased, as they are so specific in style, so I set out to make my own!

In the beginning, I was thankful to have another Vernet project maker’s experience making her boots before mine to work from. Jenni posted a two part tutorial showing how she made her boots as well as sharing information behind-the-scenes with project participants earlier in the process (Part 1 and Part 2). She closely referenced Every Lady Her Own Shoemaker, published in 1855 (a little late relative to the date of the project, but still useful for construction advice), for construction methods and carefully documented her process. In fact, she did a much better job at documenting the actual sewing than I did… I also read Anna’s information about making mid-19th century shoes multiple times to help get my mind acquainted with the project (again, a little later than the period of the project, but still helpful). She also has lots of great construction pictures.

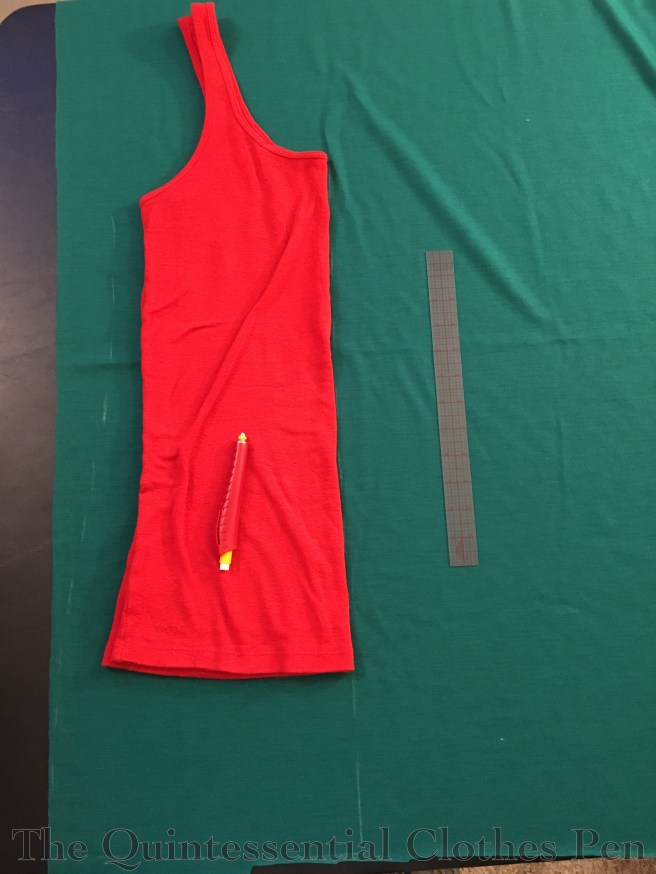

I started by creating a pattern for my shoe using patterns in Every Lady Her Own Shoemaker. Given that my shoe has the unusual turned-up-toe, I necessarily needed to make adjustments to the general slipper pattern. Here is my shoe at the mockup stage. The upper pieces fit pretty well! I adjusted the width of the sole as well as the shape of the turned-up section before moving on to cut out the final pieces.

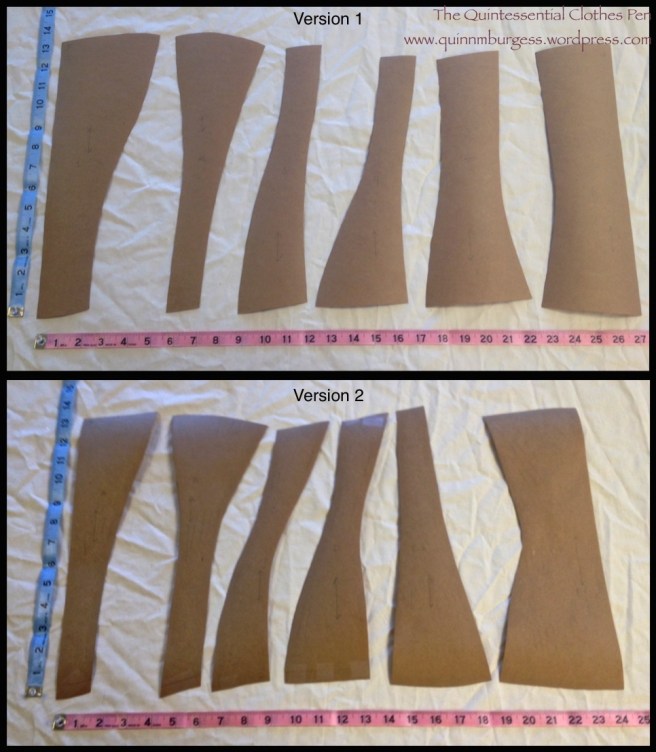

Here are all of the final pieces cut out and ready to assemble. The soles have three layers: heavier tan leather for the outer sole, cardboard for the inner sole structure, and white linen to cover the cardboard insole. The uppers have two layers: lightweight raspberry leather for the exterior and white linen for the interior. Later in the process I also added a faux fur cuff.

To help the shoes keep their turned-up-toe shape I soaked the leather soles in water, taped them to a lysol wipe container, and let them dry. You can see the results below. Not perfectly curved up, but still helpful. I also tried boiling leather soles to thicken them before shaping, but found that the leather shrank unevenly which created soles that wouldn’t work for this project. I did save them, though, and hopefully will get to use them for a future shoe making endeavor. I repeated the soaking and shaping for the cardboard insoles before gluing the linen to them. There’s a picture of the insoles at this stage in this past post.

After shaping the soles it was time to construct the uppers. I did the interior and exterior separately, then basted them together around the top opening and around the bottoms. Then I sewed the bottom edges of the uppers to the soles, using the slanting stitch through the side of the sole that Jenni shows in Part 2 of her tutorial. She used all sorts of nifty leather tools as well as a wooden last during construction. I purchased the nifty leather tools but found that they didn’t work for me and a simple non-leather needle worked just fine. (I think my leather was too thin and soft for these to be needed). As for the last, I looked online for a wooden one, never found one in my size foot, and eventually decided to give it a go without one, especially since I had to do the turned-up toe. In the end, I don’t think it was a problem not to have a last.

Once the soles were attached, I bound the front slit with matching silk ribbon. Then I cut a piece of faux fur for each shoe that went around just the top of the foot opening and could double over on itself. There are non-functional silk ribbon loops that are sewn to the front of the fur that encases the top edge of the shoe. The shoes actually close with a twill tape threaded through hand sewn eyelets on each side of the opening.

They’re actually quite comfortable for walking around in. I have very flat feet, so don’t really need arch support to be comfortable. The only thing is that my feet did get cold during our photoshoot due to the freezing ground only separated from my feet by a few thin layers of fabric. So, for the second wearing, while caroling at Christmastime, I added a faux fur insole. Problem solved! They were toasty and even more comfortable!

Interestingly, witzchouras are mentioned as being popular in Paris during the year 1827 by La Belle Assembleé, after a mention of other popular pelisses and mantles (well worth checking out!), and are are described as being worn with boots laced in front and with fur around the leg.

Doesn’t that description sound oddly familiar? It reminds me so very much of the Vernet fashion plate and my silly shoes!