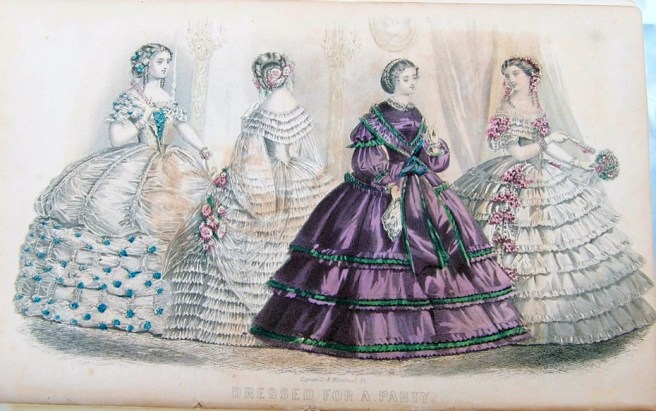

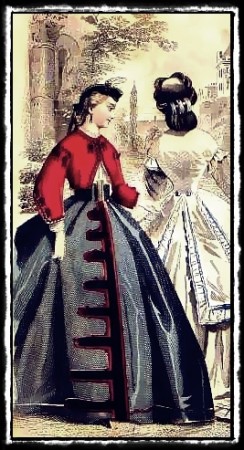

“Georgina” is the name I’ve chosen for my new 1858 cotton print day dress. Being a day dress from a new decade (the 1850s), makes her a fabulous new expansion in my wardrobe of historic clothes!

The dress is constructed from about 5yds of a Marcus Brothers reproduction historic cotton print I purchased earlier this summer. I used Past Patterns #701 and #702 bodice patterns as a starting point, though I had to make significant alterations to achieve a comfortable and pleasing fit, especially in the shoulder/armsceye area. I used the darted pattern for the fitted lining and the gathered pattern for the gathered exterior. The sleeves are the bishop sleeves from one of the patterns, though I totally changed the cuff design.

The cuff design and a lot of other fiddly details were taken from this c. 1852 dress at the Met (pictured below). If you zoom in on the cuffs on the Met website you can see that they look just like mine (pictured later in this post)! I also used the following design elements from the Met dress: piping at the neck and waist, gathers that are tacked down beyond the seam line, button closure on the cuffs, and cartridge pleating all around the skirt. I have a whole pinterest board of inspiring images for this dress and hat ensemble, but this dress is the one from which I took the most information and detail.

Here are a few pictures of the fiddly details I integrated from the Met dress:

Georgina’s bodice is lined with white cotton. There are hand sewn boning channels sewn into the bodice in the front darts on each side and on the sides. The bones are then slipped in between the layers of fabric. I didn’t have the right length metal bones, so I used heavy duty plastic wire ties–but–I cut them in half the long way so they are much skinnier than normal (they just don’t look at all historically plausible in their normal width, in my opinion). Once they’re in the bodice, you’d never know they are plastic instead of metal.

The bodice is finished at the neck and bottom edge with piping that is nicely whip stitched to the inside. There is also piping in the armsceye seam. The sleeve seams are french seamed by machine with the opening seam allowance at the cuff turned twice and stitched by hand. The other bodice seams are all machine sewn and the bodice is hand finished. The bodice closes at center front with hidden hooks and bars. It also hooks to the waistband of the skirt to keep the two pieces from gaping while worn.

The skirt has a wide hem that is hand stitched. The long skirt seams are machine sewn. The waistband is the same cotton print with an interfacing layer of canvas to create stability. The skirt is cartridge pleated and hand sewn to the waistband. There is a single layer of lightweight flannel folded into the cartridge pleats to give them a little more bulk than the thin cotton had on its own.

I also took the time to add pockets to this skirt! This turned out to be really useful for storing gloves, sunglasses, chapstick, a fan… with two pockets a lady can store so many things! Here’s how I made them and sewed them into the skirt:

Georgina cost about $18: $15 for the fabric and about $3 for hooks and eyes. The various other fabrics (cotton lining, canvas interlining, etc.) were all in my stash from previous projects (yay!). I first wore Georgina last weekend to a vintage dance performance on George’s Island in the Boston Harbor. I’ve got pictures of the performance and pictures of island exploration coming up soon!