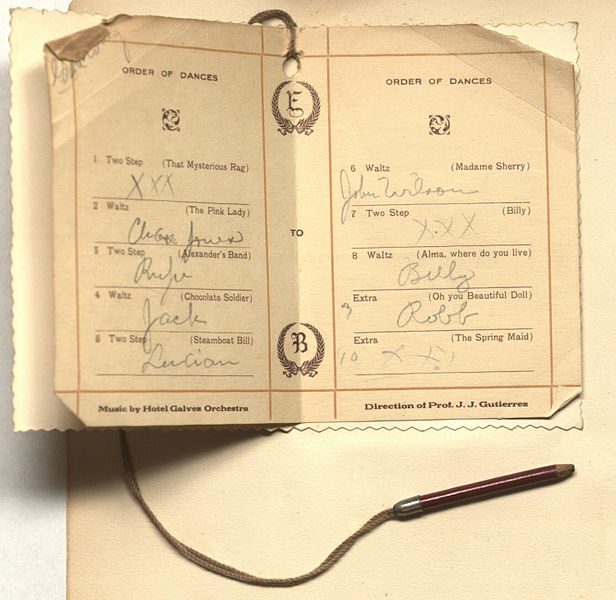

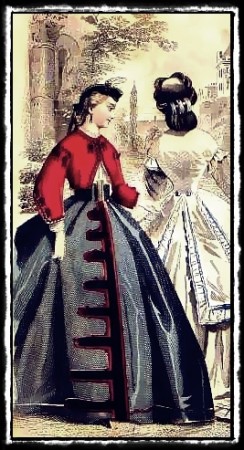

As I mentioned in my last post in this Project Journal, I decided to make a pair of stays like the one to the right. I like the unique features of these: specifically the use of colorful fabric, the fact that this is fully boned, and the cording in each seam as well as the absence of shoulder straps and tabs. I adapted a pattern from Corsets and Crinolines by Norah Waugh. The pattern I started with had straps and tabs but I eliminated those elements to reproduce the pattern of these inspirational stays.

I decided to use cane boning for these stays for a few reasons: 1) I wanted to try a new material for boning 2) cane boning is period correct for the 1780s 3) given the amount of boning needed for a fully boned pair of stays the cane boning was much more cost effective (you can see the quantity on the left–it was about $15 from Wm. Booth, Draper) and 4) the cane boning seemed like it would be super easy to manipulate and, most importantly, to cut (and it was! normal scissors easily cut the correct lengths needed and it was easy to round the ends a little bit as well!). I actually only wound up using approximately half of the cane boning that I bought, so that means that I have plenty to use for another future project!

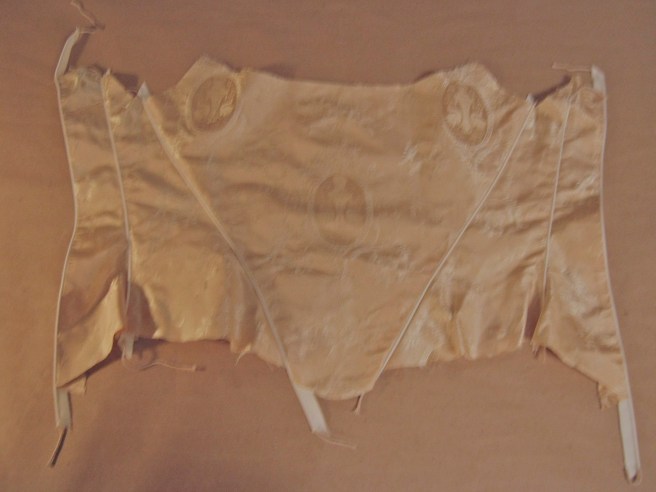

The silk that I decided to use as my exterior fabric is a fabulous damask. I originally thought about stitching my boning channels through the exterior fabric (as in my inspirational piece) but decided against that idea on this fabric, because it would really have just been way to much going on with the pattern and so many stitch lines. You can see the silk pattern a few pictures father down.

I didn’t want to stitch boning channels through my silk so I started the construction process by stitching the boning channels through two layers of cotton. You can see that I drew lines on the fabric so I could make nice, straight lines. The nice this about this is that I covered the pencil marking side with the silk, so on the inside of the finished corset all you can see is the stitching with no indication of pencil lines!

I did want my silk to roll around the center back opening on each side and then be included in the seam attaching center back to the next piece, so I stitched those silk pieces into the seams of the cotton. I just kept the silk out of the way while sewing the boning channels. Then, once the boning was complete, I stitched the remaining silk pieces to the flapping center back pieces and turned the whole thing so that the silk was on the outside with the seams facing the side of the cotton that had the pencil lines drawn on. Thus, the silk is just a covering for the cotton, it is not actually attached into the seams of the cotton except on the inside at the side back seam. You can see what I mean in the pictures below.

At this point the stays are almost finished! The last few tasks are to bind the edges (I’ll be using bias strips cut from the same cotton as the cording and lining) and work hand sewn eyelets along each side of center back. More pictures to come!